Van Halen made an extra one million dollars in the fall of 2007 when as many as 500 of the best seats at around 20 concerts on the band's reunion tour were pulled from Ticketmaster and sold through scalpers, according to a report by the Wall Street Journal. The scalpers reportedly kept about 30 percent of the jacked-up ticket prices for themselves, while the remaining 70 percent was divided between the band, their representatives and Ticketmaster itself.

The scam was part of a Ticketmaster initiative, codenamed "Project Showtime," which was designed to get a piece of the action from the scalpers, who often re-sell tickets for hundreds or thousands of dollars more than their face value. The move was part of plan to compete with a new ticketing business started by Live Nation, by offering to share profits from the scalpers with the artists and promoters.

Van Halen's 2007-2008 tour, the first with David Lee Roth on the mic in nearly a quarter century, grossed more than $90 million.

At each of the 20 shows, the best seats were taken directly out of the Ticketmaster system and passed directly to private dealers and scalpers.

The project eventually fell apart, according to the Journal, because of distrust among the participants, although a number of Van Halen tickets were sold through the scalpers.

The scam was said to be the brainchild of Van Halen manager Irving Azoff, who also now serves as Ticketmaster's CEO. Azoff is also behind the scheme to merge Ticketmaster with Live Nation, which is under review by the Justice Department. Critics and members of Congress have said that the proposed merger would create a monopoly over almost all aspects of the music business.

Ticketmaster came under fire earlier this year from Bruce Springsteen, his manager, and Springsteen's fans when customers attempting to buy Springsteen tickets at the Ticketmaster website were automatically rerouted to StubHub, a high-priced resale site owned by the company.

ETA: For source links

http://www.therockradio.com/2009/09/rep ... llion.html

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB125141597320965247.html

OT: Van Halen earned extra 1$ million from scalped tickets

28 posts

• Page 1 of 2 • 1, 2

OT: Van Halen earned extra 1$ million from scalped tickets

Last edited by animal on 03 Sep 2009 02:44, edited 1 time in total.

A mind full of useless information.

Quotes are my speciality.

I am the YouTube Whisperer

Quotes are my speciality.

I am the YouTube Whisperer

-

animal - Posts: 2641

- Joined: 04 Feb 2006 02:18

- Location: Savoring the Book.

Re: OT: Van Halen earned extra 1$ million from scalped tickets

Wow.

You got a source link, Animal?

You got a source link, Animal?

Dramatic highlights & a unique musical cosmos. Guaranteed.

-

DirtyMartini - Posts: 9622

- Joined: 03 Mar 2007 18:38

- Location: Around.

Re: OT: Van Halen earned extra 1$ million from scalped tickets

DirtyMartini wrote:Wow.

You got a source link, Animal?

http://www.therockradio.com/2009/09/rep ... llion.html

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB125141597320965247.html

By ETHAN SMITH

Before Ticketmaster Entertainment Inc., the nation's leading ticket seller, and Live Nation Inc. decided to merge, Ticketmaster pursued a strategy to thwart the concert promoter's plan to enter the ticket-selling business, according to several people familiar with the matter. Spearheaded by Irving Azoff, Ticketmaster's current chief executive, the effort sought to combine several of the nation's biggest ticket scalpers with Ticketmaster and other major concert-industry players. At the time, Mr. Azoff was the CEO of Front Line Management, which handles dozens of top musical acts and was partly owned by Ticketmaster.

Irving Azoff

The goal of the initiative, codenamed "Project Showtime," was to capture a piece of the sky-high prices charged by scalpers, which can exceed a ticket's face value by hundreds, or even thousands, of dollars. They could then compete against Live Nation's nascent ticketing business by offering to share the scalpers' revenue with entertainers and venues.

Others involved in the talks included AEG Live, the largest concert promoter after Live Nation, and MSG Entertainment, which owns Madison Square Garden.

After months of talks, the initiative against Live Nation -- which back then was in effect positioning itself as a competitor of both Ticketmaster and the brokers -- fell apart amid mutual distrust, according to people familiar with the matter. Neither side was confident it would get accurate accounting from the other. Nonetheless, the plan sheds light on the motives behind the current merger, whose antitrust implications are currently under review by the Justice Department.

The proposed merger between Live Nation and Ticketmaster would join the two former rivals and also create a more efficient way to realize many of the financial benefits Ticketmaster would have received if it had teamed up with the brokers. A combined company could set prices that are closer to what the market will bear, according to people familiar with the company's strategy, allowing it to snag much of the money that currently flows to scalpers.

"Ticketmaster continually explores new and viable revenue streams in both the primary and secondary marketplace on behalf of our clients and live event rightsholders," a Ticketmaster spokesman said. He cited numerous ways the company has sought "to maximize sales and capture the fair market ticket value for promoters, venues, teams and artists."

Testifying before the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Courts and Competition earlier this year, Live Nation CEO Michael Rapino cited all the money flowing to the burgeoning scalping industry as a key rationale for the merger. "[Scalping] is about a billion-dollar business that we receive zero dollars from," Mr. Rapino complained. "We spend millions on real-estate and artist investments, and we realize zero of the scalping market."

Scalpers, who prefer to be called brokers, are worried that the merger could run them out of business. "If this merger were to go through, the secondary market for concert tickets as we know it would cease to exist," predicts Paul McCann, a ticket broker near Baltimore who was not involved in the Project Showtime talks. "They would replace it with something they create, and they will keep all the money the secondary market generates."

The attempt to create Project Showtime got started with a meeting at Ticketmaster's West Hollywood, Calif., headquarters in the summer of 2007. It was led by Mr. Azoff, who opened with a joke. "I always knew we'd end up in a room together," he told the assembled brokers, according to people with knowledge of the meeting. "I just thought it would be a courtroom."

Present at the meeting, according to these people, were senior executives of AEG Live, Ticketmaster and Cablevision Systems Corp.'s MSG Entertainment, which owns Madison Square Garden and Radio City Music Hall. Spokesmen for AEG and MSG Entertainment declined to comment.

The brokers at the meeting were the owners of Boston-based Ace Ticket; Los Angeles's Barry's Tickets Service; Fort Lauderdale's Total Tickets; Chicago's Gold Coast Tickets; New York City's Elite Ticket Service; and Alliance Tickets, which operates in Denver, Las Vegas and Seattle.

Promoters and others in the mainstream concert business have long looked with envy at the steep markups scalpers charge for hot concerts. The Internet has made such resales easier and even more lucrative, allowing brokers to buy tickets for events in distant cities and list them on Web sites like eBay Inc.'s StubHub.com. But brokers can also be left holding the bag when they bet big on a show that flops or an outdoor event that is rained out.

Under the plan, the consortium led by Ticketmaster and its then-parent, IAC/InterActiveCorp., was to acquire the six regional ticket brokers for as much as $25 million apiece and give them seats on the new venture's board. (Ticketmaster was spun off last year by IAC and subsequently acquired a majority stake in Mr. Azoff's Front Line Management, installing him as CEO of the combined entity. A spokeswoman for IAC declined to comment.)

Mr. Azoff and the other executives emphasized "how big it was going to be, how it was going to crush Live Nation," recalls a person who attended. "We'd go forward and make lots and lots of money." At a dinner later, Timothy B. Schmit, a member of the Eagles, one of Mr. Azoff's longtime management clients, stopped by.

There was even a test run in the fall of 2007, according to numerous people with knowledge of the matter. Up to 500 of the best seats to each of about 20 concerts by Van Halen, the veteran hard-rock band managed by Mr. Azoff, were pulled from the Ticketmaster system and passed directly to the brokers being considered for acquisition.

The brokers kept 30% of the marked-up sale price for themselves, and the remaining 70% was divided among Ticketmaster, the band and its handlers. The band netted an extra $1 million, at least, from the arrangement, according to people familiar with the matter. A spokesman said the band wasn't available for comment.

But Ticketmaster executives were ultimately wary of going into business with the leaders of an industry they had long opposed.

The company briefly explored another avenue into the secondary market, paying $265 million last year for a ticket-resale site called TicketsNow.

Ticketmaster is now trying to sell that Web site, and people familiar with the situation say the company ultimately decided the merger would allow it to achieve many of the same goals as buying the ticket brokers.

Just last week, Ticketmaster also opened another front in its battle against scalpers, initiating a new technology that blocks any computer that attempts to access the company's Web site 1,000 times or more in a day, a frequency achieved by some professional scalpers using special computer software. The move is likely to further heighten tensions with brokers.

A spokesman for Ticketmaster said, "We regularly take measures to protect the security of our Web site and system to enforce our terms of use."

Write to Ethan Smith at ethan.smith@wsj.com

Printed in The Wall Street Journal, page B1

A mind full of useless information.

Quotes are my speciality.

I am the YouTube Whisperer

Quotes are my speciality.

I am the YouTube Whisperer

-

animal - Posts: 2641

- Joined: 04 Feb 2006 02:18

- Location: Savoring the Book.

Re: OT: Van Halen earned extra 1$ million from scalped tickets

WHERE are the LAWSUITS?!

Seriously.

Always good to see you around, Animal...

Seriously.

Always good to see you around, Animal...

On Google - site:stewartcopeland.net "your keyword here" - thanks DM!!

-

Divemistress of the Dark - Posts: 7873

- Joined: 12 Jul 2006 14:10

- Location: Nashville, TN

Re: OT: Van Halen earned extra 1$ million from scalped tickets

I wonder how many other bands and artists are doing this too.

“...and er, did anyone try just pushing this little red button?”

-

Mrs. Gradenko - Posts: 3522

- Joined: 18 Apr 2005 06:35

- Location: Phenomenal Brat

Re: OT: Van Halen earned extra 1$ million from scalped tickets

Thanks for posting this. I was meaning to post the article since I first read it since there has been much discussion and interest around here on this subject and just didn't get around to it.

Once again the audacity of Irving Azoff just floors me.

Another great article by the WSJ in covering this subject which ,seems to me, the overall media for some reason doesn't show much interest in covering.

Once again the audacity of Irving Azoff just floors me.

Another great article by the WSJ in covering this subject which ,seems to me, the overall media for some reason doesn't show much interest in covering.

Have we got touchdown

-

Throb - Posts: 1162

- Joined: 13 Jul 2007 02:47

- Location: 1983

Re: OT: Van Halen earned extra 1$ million from scalped tickets

I have suspected for a long time that artists somehow get a piece of the scalpers' action because it didn't make sense to me that so few of them made much noise about it. Pearl Jam was a rare exception years ago and I don't remember seeing anyone major backing them up.

-

Susan - Posts: 1726

- Joined: 13 Jul 2007 02:27

- Location: Wishing STEWART a happy birthday!

Re: OT: Van Halen earned extra 1$ million from scalped tickets

The Robber Baron Scumbags ride again.

-

zilboy - Posts: 1030

- Joined: 07 Jan 2006 18:42

Re: OT: Van Halen earned extra 1$ million from scalped tickets

You do wonder how common this is.

Also, there are a wide variety of anti-scalping laws. I wonder if TicketBastard or Van Halen were parties to an illegal act in some states.

Pretty disgusting for Van Halen to do this and yet another sign of the evilness of TicketBastard.

Reminded (again) of the lines from the Simpsons:

[quote]Mr. Burns: (chuckles) And to think, Smithers, you laughed when I bought TicketMaster. "Nobody's going to pay a 100% service charge."

Smithers: Well, it's a policy that ensures a healthy mix of the rich and the ignorant, sir. [/quote]

Also, there are a wide variety of anti-scalping laws. I wonder if TicketBastard or Van Halen were parties to an illegal act in some states.

Pretty disgusting for Van Halen to do this and yet another sign of the evilness of TicketBastard.

Reminded (again) of the lines from the Simpsons:

[quote]Mr. Burns: (chuckles) And to think, Smithers, you laughed when I bought TicketMaster. "Nobody's going to pay a 100% service charge."

Smithers: Well, it's a policy that ensures a healthy mix of the rich and the ignorant, sir. [/quote]

SC-There are a few crazy people on this planet. Sure sign of that is that they kinda like my music

-

njperry - Posts: 2512

- Joined: 25 Feb 2008 23:42

- Location: Never too young for Stewart soundtracks

Re: OT: Van Halen earned extra 1$ million from scalped tickets

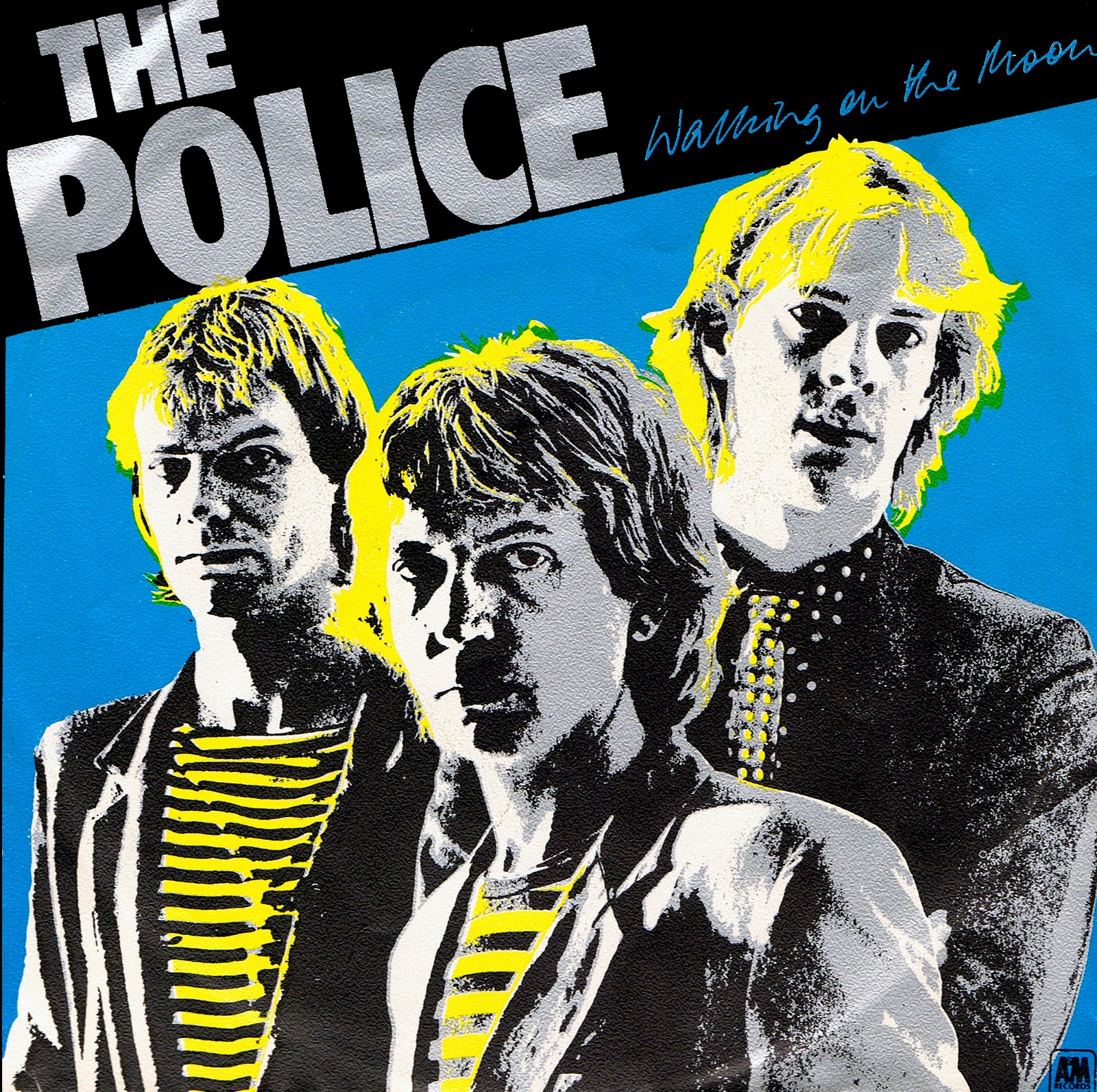

This is very common and was done on .........The Police tour.

rock and roll baby.

rock and roll baby.

- garyq

- Posts: 30

- Joined: 03 Feb 2007 18:14

- Location: canada

Re: OT: Van Halen earned extra 1$ million from scalped tickets

And you know this, how?

Sorry, it's just a serious allegation to make, and some proof other than "your cousin's friend told you" might be appreciated.

Sorry, it's just a serious allegation to make, and some proof other than "your cousin's friend told you" might be appreciated.

On Google - site:stewartcopeland.net "your keyword here" - thanks DM!!

-

Divemistress of the Dark - Posts: 7873

- Joined: 12 Jul 2006 14:10

- Location: Nashville, TN

Re: OT: Van Halen earned extra 1$ million from scalped tickets

None of this shocks me anymore.

The whole industry is corrupt as fuck.

I'd bet that the list of bands who haven't before would be slim to none.

Heck, some of them are probably reaping it and don't even know it.

The whole industry is corrupt as fuck.

I'd bet that the list of bands who haven't before would be slim to none.

Heck, some of them are probably reaping it and don't even know it.

I don't wanna work, I just wanna bang on the drums all day.

- Tamadude

- Posts: 1547

- Joined: 05 Jun 2007 03:55

Re: OT: Van Halen earned extra 1$ million from scalped tickets

[quote="Divemistress of the Dark"]And you know this, how?

Sorry, it's just a serious allegation to make, and some proof other than "your cousin's friend told you" might be appreciated.[/quote]

Where you think scalpers get their tickets? 7-11?

Sorry, it's just a serious allegation to make, and some proof other than "your cousin's friend told you" might be appreciated.[/quote]

Where you think scalpers get their tickets? 7-11?

- garyq

- Posts: 30

- Joined: 03 Feb 2007 18:14

- Location: canada

Re: OT: Van Halen earned extra 1$ million from scalped tickets

Tamadude wrote:None of this shocks me anymore.

The whole industry is corrupt as fuck.

I'd bet that the list of bands who haven't before would be slim to none.

Heck, some of them are probably reaping it and don't even know it.

Well that's it...how many even know the details of what goes on? Some probably don't give it much thought. It is on our minds because we've been there in front of the computer, seeing the message "your wait time is 15 minutes or more, you're fucked."

But I don't think your average rock star has trouble getting into a show he wants to see. Do you think Springsteen sat in front of his computer in New Jersey when the final Police show went on sale? So it's not in the top of their minds.

Earlier this year when some shit hit the fan, and then the news was breaking about the pending Live Nation/Ticketbastard merger reporters tried to get Bono to comment on it...he had NO opinion and didn't know enough about the issue to comment. Now I think the world of Bono and am a lifelong U2 fan but give me a break, since when does he not have an opinion? I gotta hand it to the Chicago reporter who didn't let him off too easily! Granted, Bono spends a lot of time on other serious issues, and he's got a wife/children/business/life, but it struck me as funny.

http://blogs.suntimes.com/derogatis/200 ... ive_n.html

I thought it was also interesting that he was worried about songwriters getting paid (fair enough of course) but not about getting maximum payment for PERFORMANCE and TOUR. If I sell my $98 ticket for $300 and keep that money..yay for me, but U2 doesn't see any of that money. And they don't mind? Really? But if I download their $15 album without paying for it, that's a problem? Maybe I am missing something.

Or is it easier to worry about those individuals who download than take on large corporations? (for the record, I pay for my music except the live stuff that gets posted around).

I don't think that most touring bands have much of a choice, however, if they want to ensure that a maximum number of fans get to see them on tour it seems they are stuck.

Even if one "knows," who's going to go first in taking it down? Pearl Jam tried and look where that got them.

The Police made it work out by having the fan club presales (not perfect but we did get tickets) and enough shows that eventually the demand was a bit lower and it got easier as it went on.

-

Susan - Posts: 1726

- Joined: 13 Jul 2007 02:27

- Location: Wishing STEWART a happy birthday!

28 posts

• Page 1 of 2 • 1, 2

Who is online

Users browsing this forum: No registered users and 40 guests